This article is about Data Science

Part 2: The Quest for Artificial intelligence - The Deep Blue story

By Balasubramaniam N

Published on 11/09/2019

12 minutes

In the annals of chess history, Kasparov is considered the greatest chess player. For twenty years, from 1985 when he started playing the game professionally to 2005 - when he retired from the arena, Kasparov was virtually undefeated. At the age of twenty-two, he beat Anatoly Karpov (another Russian) to become the youngest World Champion, a position he held for two decades. He was not merely the greatest strategist the game has ever known, but Kasparov’s ability to outthink the opponent by several moves, sudden bursts of unconventional play, and a calculated arrogance that unnerved his opponents. He was a recluse, self-centered, introverted and almost disdainful of everyone else. Like Mohammad Ali in boxing, Kasparov believed that there was no other in the world who can be his equal. If winning a game of chess is the true measure of intelligence in a machine, then beating Kasparov will be the crown jewel of any such effort. IBM was willing to invest in that challenge.

It was a calculated move by IBM. If it paid off, then, once again, IBM would be applauded for ushering in the new wave of Information technology. If it failed, there was nothing to lose. After all, Kasparov was expected to win. In the May 1997 edition of Newsweek, Steven Levy, the renowned journalist and chronicler of technology persuaded the magazine’s editors to run a cover page featuring Kasparov vs Machine match. Reluctantly, the editors agreed to publish the legendary cover line “The Brain’s Last Stand” with a picture of a serious looking Kasparov peering at the reader. Fortunately, there were no celebrity deaths, or political upheavals that week. Therefore the May edition was well received by the reading public, and an active appetite generated for the tournament to follow.

In 1996, when Kasparov played the first version of Deep Blue in Philadelphia, he beat the machine easily with a final score of 4-2. The IBM team huddled for the next thirteen months fixing the algorithm, feeding the machine with more refined datasets, and bolstering the computational powered. By May of 1997, Deep Blue was a different beast altogether, and hundred times more powerful and tuned to play chess. In the rematch of 1997, Kasparov would play six games, with all the rules of the game in place, including the time controls. Based on machine’s advice, a computer scientist from IBM’s Stuart Campbell, would move the piece on the chess board. Kasparov won the first game quite easily in forty-five moves using the Kings Indian attack - a classic chess opening normally employed by champions. Going into game two, Kasparov was on a roll and confident.

On the 36th move, Kasparov left his queen exposed for his opponent to take. It was part of the Smyslov variation strategy, and most other players would have taken the queen and played to the script. But Deep Blue came up with a very unusual and subtle move that caught Kasparov off guard. It left the queen alone and moved the pawn. In that single move, IBM’s Deep Blue had demonstrated an ability outthink and plan beyond the most accomplished strategist of the game. In an interview after the game (and years later too), Kasparov would isolate that 36th move as his moment of realization and awakening. After that move, Kasparov began to become conscious of his game plan, and little agitated too. Within fifteen more moves, Kasparov conceded the game and give Deep Blue its first victory in the tournament.

Kasparov later cried foul, and demanded that IBM show him detailed logs of the moves. IBM produced snippets of the logs, but never showed the world the whole piece. Many years after the fire of the controversy cooled down, IBM revealed that in the second game Deep Blue’s 36th move of the game was actually algorithmically flawed, totally unintended, and never part of the strategy. An inadvertent computer error cost Kasparov his cool, and the game itself.

The next three games were drawn, and the outcome of the last game - the sixth would be the decider. Kasparov opened the game with the Caro-Kann defense which would require a sacrifice of the knights by opponent without any immediate gains. Kasparov reasoned that a machine wouldn’t play that move because it did not lead to any strategic advantages; but to his surprise, Deep Blue did make the Knight’s sacrifice as required and willing to wait for a subsequent opening. What Kasparov didn’t know at the time he played was that very morning of the last game IBM programmers had fed the Caro-Kann variations into Deep Blue. The machine was prepared for the bait. Kasparov resigned in more twenty moves, and Deep Blue had scored an improbable victory over the champion, and the human mind, so to speak.

In writing this article, I have condensed large tracts of material to make it more accessible to a general reader. The triumph of Deep Blue in 1997 ushered in a new age of confidence in the world of Information technology. Within a few years, Google would be born, and along with Apple and Microsoft, would transform the social landscape of how data can be processed and used. Kasparov himself practiced and refined his skills against computer simulated games, but in the end, the very machine that supported his practice humbled his pride.

Of course, there was a huge human team behind Deep Blue’s success that trained the machine not merely to be superiorly efficient in computation but a little cunning and deceptive too.

For instance, they programmed Deep Blue to slow down on crucial moves, and prolong the act of making the move, to induce a sense of indecision and uncertainty. And on other times, when the opponent makes a crucial move, the machine would react spontaneously. As a machine, a human would expect consistent responses from it, but by deliberately varying the response times, the designers were attempting to wage a psychological warfare with the opponent. And that’s the scary part of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Somewhere along the line, we painfully realize that machines don’t possess any intelligence or knowing. It is we who give it direction and “intention”.

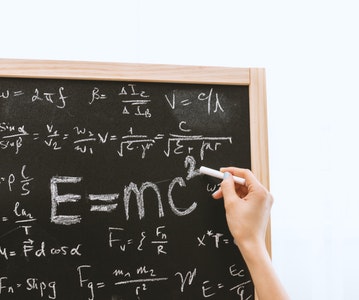

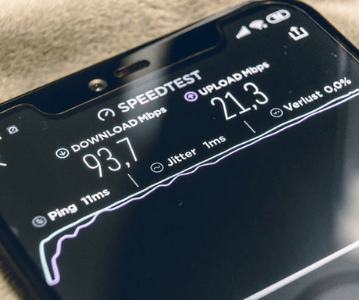

The other factor that must be borne in mind is that chess is all about comparing the value of a move in relation to the coins on the board. The rules of the game can be symbolized in mathematical terms and assigning appropriate weights to each move. A robust algorithm can be built that can minutely compute, factor and compares results and patterns from its repository to produce the next move. If a given move builds confidence in the algorithm of the machine’s chances of a win, it is deemed a numerical victory, otherwise not. Highly-trained human brains - such as Kasparov or Viswanathan Anand’s - are capable of holding and visualizing the outcomes of their moves at least five to ten steps ahead. How the brain does it is still a mystery, and computers are nowhere close to emulating the nimbleness and subtlety of the brain in arriving at such a visualization. But computers make up in computational speed and tireless efficiency what it lacks in the human ability to visualize. Deep Blue is the perfect manifestation of such a machine.

After Deep Blue’s stunning victory, when the euphoria settled down, the important question arose on what really was the achievement here. Did we concede that machines can be intelligent in a way humans are, not just in playing chess, but in all other aspects as well? Or was Deep Blue’s victory merely an exaggerated attempt at mastering a specified skill which we seem to effortlessly exhibit with some practice? Is Artificial Intelligence the right phrase at all to describe what Deep Blue had achieved? Or were we simply carried away by what we got the machine to achieve.

Broader questions on what it means to be intelligent, or understanding language in all its nuances, or create intellectual abstractions, or create art - still seemed beyond the ken of AI. The Deep Blue story belong to the last decade of the twentieth century. The twenty-first century has radically improved upon the capabilities of Deep Blue, and with each passing day, we seem to take over more and more of specialized computational tasks from Human hands. However, we are still very far away from creating a mechanical prototype equivalent to the complexity, intricacy and elasticity of the human brain. In 2011, IBM unleashed Watson, another significant advancement over Deep Blue, this time around, the machine was equipped to understand human language and respond to clues.

About the Author

Balasubramaniam N has more than 25 years of experience in IT, with special emphasis on programming languages and databases. In the last decade Bala has focused on evangelizing the full stack development along with platforms, tools and techniques for Big Data and Data Analytics. Bala is passionate about training and has supported the training needs of customers across the globe in skilling their employees to work of specific projects, and in demonstrating Proof of concept (POC) in transforming business processes using refined technical toolsets. At NIIT, Bala heads the Center of excellence for technology for the Corporate learning business, and also leads the Tech Academy - an internal initiative in skilling a qualified pool of mentors across domains. He continues to teach as much he can.

Advanced PGP in Data Science and Machine Learning (Full Time)

Become an industry-ready StackRoute Certified Data Science professional through immersive learning of Data Analysis and Visualization, ML models, Forecasting & Predicting Models, NLP, Deep Learning and more with this Job-Assured Program with a minimum CTC of ₹5LPA*.

Job Assured Program*

Practitioner Designed

Sign Up

Sign Up